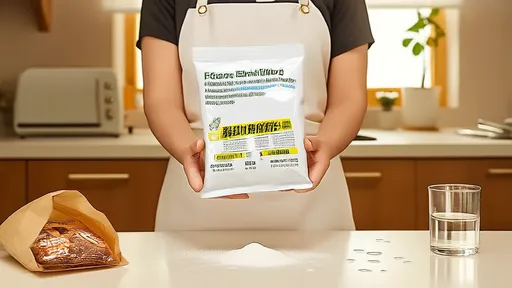

The internet has been buzzing with viral videos showing food desiccants exploding upon contact with water. These dramatic clips have raised alarms among consumers, leaving many to wonder: just how dangerous are these common household items? While the chemical reaction may look terrifying in controlled social media experiments, the real-world risks depend heavily on context, product composition, and handling practices.

Food desiccants – those small packets marked "DO NOT EAT" found in everything from beef jerky to new shoes – serve the crucial purpose of absorbing moisture to prolong shelf life. The most controversial variety contains calcium oxide (quicklime), which reacts violently with water in an exothermic reaction. When confined in a sealed container, this rapid release of carbon dioxide gas can indeed cause what appears to be an explosion. However, industry experts emphasize that the actual hazard level depends on multiple factors often omitted from sensationalized online content.

Understanding the chemistry behind these viral demonstrations reveals why they don't represent typical household scenarios. A controlled experiment using pure calcium oxide in large quantities within a sealed soda bottle creates perfect conditions for dramatic pressure buildup. In reality, food-safe desiccant packets contain only a few grams of material and are designed with breathable packaging that prevents dangerous pressure accumulation. The American Chemistry Council notes there have been zero reported cases of these packets exploding during normal use over the past decade.

That said, certain reckless behaviors can elevate risks substantially. Teenagers attempting to recreate viral "desiccant bomb" challenges by combining multiple packets in glass bottles have suffered burns and eye injuries. Pediatricians report more frequent cases of children rupturing packets out of curiosity, leading to chemical burns when the powder contacts moist skin or eyes. Unlike the controlled explosions shown online, these real-world incidents typically involve thermal burns rather than concussive force.

The manufacturing industry has responded to safety concerns with improved designs. Many companies now use silica gel (which poses minimal reaction risk) instead of calcium oxide, while others employ multilayer packaging that prevents accidental exposure. Some European manufacturers have introduced food-grade desiccants that turn bright colors when exposed to moisture, providing visual warnings before significant heat generation occurs. These innovations reflect an evolving understanding of consumer safety in product design.

Medical toxicologists offer practical advice for households containing these products. Keeping desiccant packets away from children's reach goes without saying, but adults should also avoid cutting them open or submerging them in liquids. If exposure occurs, flushing affected areas with cool running water for 15-20 minutes remains the gold standard first aid response. Contrary to some online misinformation, the reaction byproducts aren't toxic – the primary danger comes from thermal injury rather than chemical poisoning.

Regulatory bodies approach desiccant safety from different angles. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission classifies them as industrial chemicals rather than consumer products, creating a regulatory gray area. Meanwhile, the FDA focuses on food-contact safety rather than reaction hazards. This fragmented oversight explains why warning labels vary significantly between manufacturers. Some consumer advocates are pushing for standardized "reactive chemical" warnings similar to those on drain cleaners or other household hazards.

As with many viral phenomena, the truth about food desiccant dangers lies between extreme portrayals. While the chemical reaction can theoretically generate enough heat to ignite paper (approximately 150°C/300°F in optimal conditions), everyday scenarios rarely permit such intense heat buildup. Fire marshals confirm that desiccant-related fires are extraordinarily rare compared to other household chemical incidents. The greater risk may actually be psychological – the viral videos have spawned unnecessary panic, with some consumers discarding perfectly safe food products at the mere sight of a desiccant packet.

Looking forward, material scientists are developing next-generation desiccants that eliminate reaction risks entirely. One promising alternative uses modified cellulose fibers that absorb moisture without exothermic reactions. Another approach embeds moisture-absorbing minerals in polymer matrices that prevent direct water contact. While these innovations may eventually make the current controversy obsolete, for now, educated handling remains the best defense against both real and exaggerated dangers.

The viral "exploding desiccant" trend ultimately serves as a case study in how social media distills complex chemical concepts into shareable – if misleading – content. Rather than fearing these ubiquitous packets, consumers should respect them as the mild household hazards they truly are: more dangerous than a silica bead pillow, but far less risky than a bottle of bleach. As with any chemical product, the antidote to both complacency and panic is measured, science-based understanding.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025