The recent incident of a coolant leak on the International Space Station (ISS) has once again brought the growing threat of space debris into sharp focus. While the immediate cause of the leak is still under investigation, early reports suggest that a micrometeoroid or a piece of orbital debris may have been responsible. This event underscores a much larger and more pressing issue: the ever-increasing cloud of man-made objects circling Earth, posing risks not only to spacecraft but also to the future of space exploration.

Space debris, often referred to as "space junk," consists of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments from collisions or explosions. Over decades of space activity, this debris has accumulated to alarming levels. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that there are over 36,000 objects larger than 10 cm in orbit, along with millions of smaller pieces that are too tiny to track but still capable of causing significant damage. The velocity at which these objects travel—up to 28,000 kilometers per hour—means even a paint chip can crack a spacecraft's window or puncture its hull.

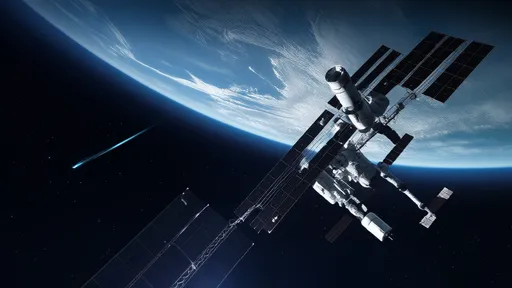

The ISS, a symbol of international cooperation and scientific progress, is particularly vulnerable. Orbiting at an altitude of approximately 400 kilometers, it regularly maneuvers to avoid larger pieces of debris. However, smaller fragments are impossible to track reliably, leaving the station and its crew at constant risk. The recent leak, though not catastrophic, serves as a stark reminder of what could happen if a larger object were to strike a critical component. The consequences could range from life-support system failures to a complete loss of the station.

Beyond the ISS, the proliferation of space debris threatens all orbital activities. Commercial satellites, which provide essential services like communication, weather forecasting, and navigation, are also at risk. A single collision can generate thousands of new fragments, exacerbating the problem in a cascading effect known as the Kessler Syndrome. Proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978, this scenario describes a chain reaction of collisions that could render certain orbits unusable for generations. Some experts worry that we are already approaching this tipping point.

Efforts to mitigate the space debris problem have been slow to materialize. International guidelines, such as the United Nations' Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, recommend measures like deorbiting satellites at the end of their operational lives. However, compliance is voluntary, and enforcement is virtually nonexistent. Meanwhile, the rapid growth of commercial space ventures, including mega-constellations of satellites, has added thousands more objects to an already crowded environment. Companies like SpaceX and OneWeb have launched hundreds of satellites in recent years, with plans for thousands more.

Technological solutions are being explored, but none offer a quick fix. Proposed methods include using lasers to nudge debris out of orbit, deploying robotic arms to capture and remove large objects, and designing satellites with built-in disposal mechanisms. While promising, these approaches are still in experimental stages and face significant technical and financial hurdles. In the meantime, the debris continues to accumulate, and the risk of collisions grows.

The political and economic challenges are just as daunting as the technical ones. Space-faring nations have competing interests, and there is little consensus on how to address the issue collectively. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which forms the basis of international space law, is ill-equipped to handle modern challenges like debris removal. Questions about liability, jurisdiction, and funding remain unresolved, leaving the international community in a state of paralysis.

As the recent ISS incident demonstrates, the space debris crisis is no longer a theoretical concern—it is a present and escalating danger. Without urgent action, the dream of expanding humanity's presence in space could be jeopardized. The leak may have been a minor setback, but it should serve as a wake-up call. The window to prevent a catastrophic chain reaction is closing, and the time to act is now.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025